|

|---|

| From the Shield on an 1851 One Thirteenth of a Shilling |

During this period, many newspaper articles discussed the state of Jersey's coinage and bank notes. Many were written complaining about the lack of coins, the confusion between 12 and 13 pence, foreign coins, and the "Reign of Rags." Things to note about this series:

For a quick look at the mintage figures, visit the “Mintage Information” site.

|

|

| From the Times of London, November 13, 1844 |

|

|

|

to review the die varieties or

the letter icon

to review the die varieties or

the letter icon  to see images using a digital microscope.

to see images using a digital microscope.

| Posthumous medallic portrait of William Wyon by his son L. C. Wyon 1854 (click on image to enlarge) | |

|---|---|

|

|

| The name of William Wyon is well known among coin and medal collectors because of his prodigious output and artistic skill.

For Jersey, he designed these copper coins. |

|

| One Fifty-Second of a Shilling 1841 and 1861 (click on image to enlarge) | |

|---|---|

|

|

Year J# KM# Mintage Diameter

1841 57 1 116,480 21.90

1861 58 Proof Only 21.90

1861 58 Proof Only 21.90

|

| One Twenty-Sixth of a Shilling 1841, 1844, 1851, 1858, and 1861 (click on image to enlarge) | |

|---|---|

|

|

Year J# KM# Mintage Diameter

1841 34 2 232,960 28.10

1844 35 232,960 28.20

1844 35 232,960 28.20

1851 36 173,333 28.25

1851 36 173,333 28.25

1858 37 173,333 28.15

1858 37 173,333 28.15

1861 38 173,333 28.20

1861 38 173,333 28.20

|

|

| The Royal Squadron entering St Aubin's Bay by Philip John Ouless for the Queen's visit to Jersey in 1846 |

|

| From the Times of London, October 28, 1844 |

| One Thirteenth of a Shilling 1841, 1844, 1851, 1858, and 1861 (click on image to enlarge) | |

|---|---|

|

|

Year J# KM# Mintage Diameter

1841 3 3 116,480 34.15

1844 4 145,600 34.10

1844 4 145,600 34.10

1851 5 173,333 34.15

1851 5 173,333 34.15

1858 6 173,333 34.10

1858 6 173,333 34.10

1861 7 173,333 34.15

1861 7 173,333 34.15

1865 8 Proof Only 34.15

1865 8 Proof Only 34.15

As with several other Jersey coins, there seems to be a difference of opinion on the correct mintage figures for the Jersey 1844 penny. In his book, The Coins of the British Commonwealth of Nations Part 1, European Territories, Major F. Pridmore states that the mintage of the 1844 Jersey one thirteenth of a shilling as 27,040. The 1841 had 116,480 coins minted, while the other issues each had a mintage of 173,333. This would make the 1844 the key of the series. Krause and other leading publications have repeated these numbers. However, according to Royal Mint documents, the correct mintage figure is 145,600. Things to note:

|

|

| From the Times of London, November 22, 1841 |

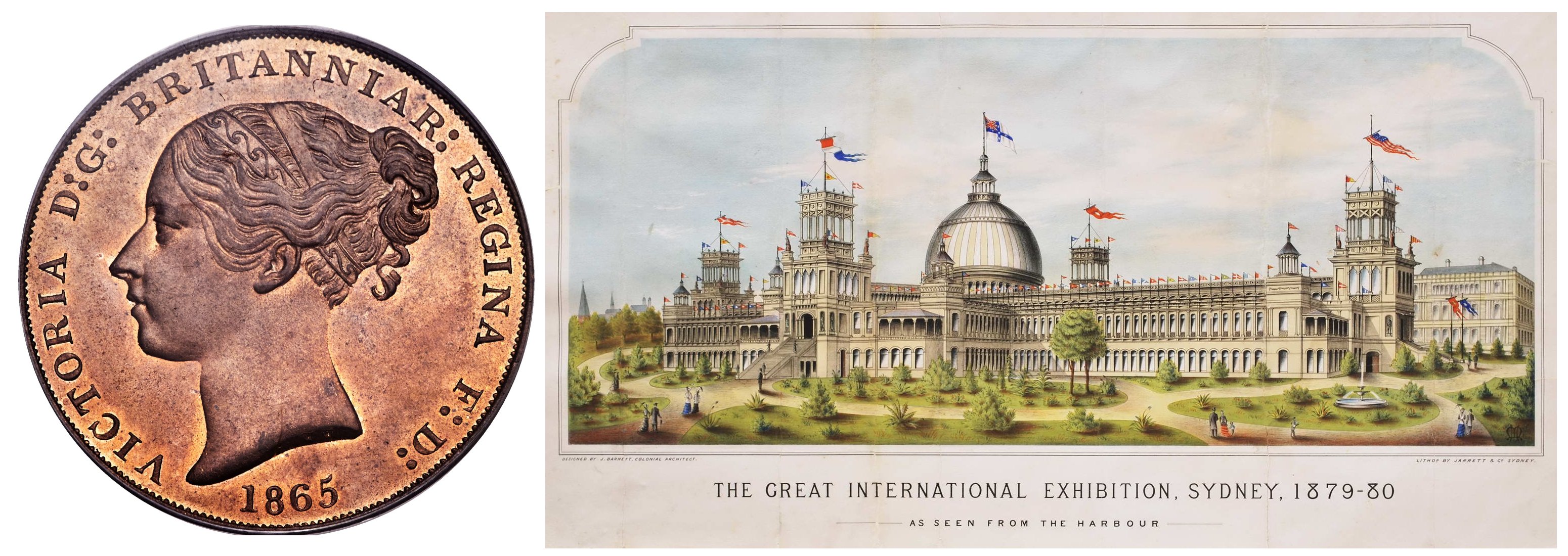

| The 1865 Proof Coin and The Great International Exhibition in Sydney, Australia of 1879-1880 |

|---|

|

It is interesting to note that there were restrikes of several Jersey proof coins minted in 1879 for the Sydney International Exhibition of 1879-1880.

The noted numismatist, Howard Hodgson writes in the 2023 British Numismatic Journal10:

The coins sent out for the Exhibition by the Royal Mint in London were all proofs and there were two of each piece. They included ‘type’ specimens of Imperial coinage of Queen Victoria, including two 'Una and the Lion' £5 pieces of 1839. There were also representative sets of colonial coins, comprising specimens from Canada (plus its preconfederation provinces of New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island), Cyprus, Hong Kong, the Isle of Man, Gibraltar, Jamaica, Jersey, Mauritius, the Straits Settlements and certain other colonies. … |

|

|

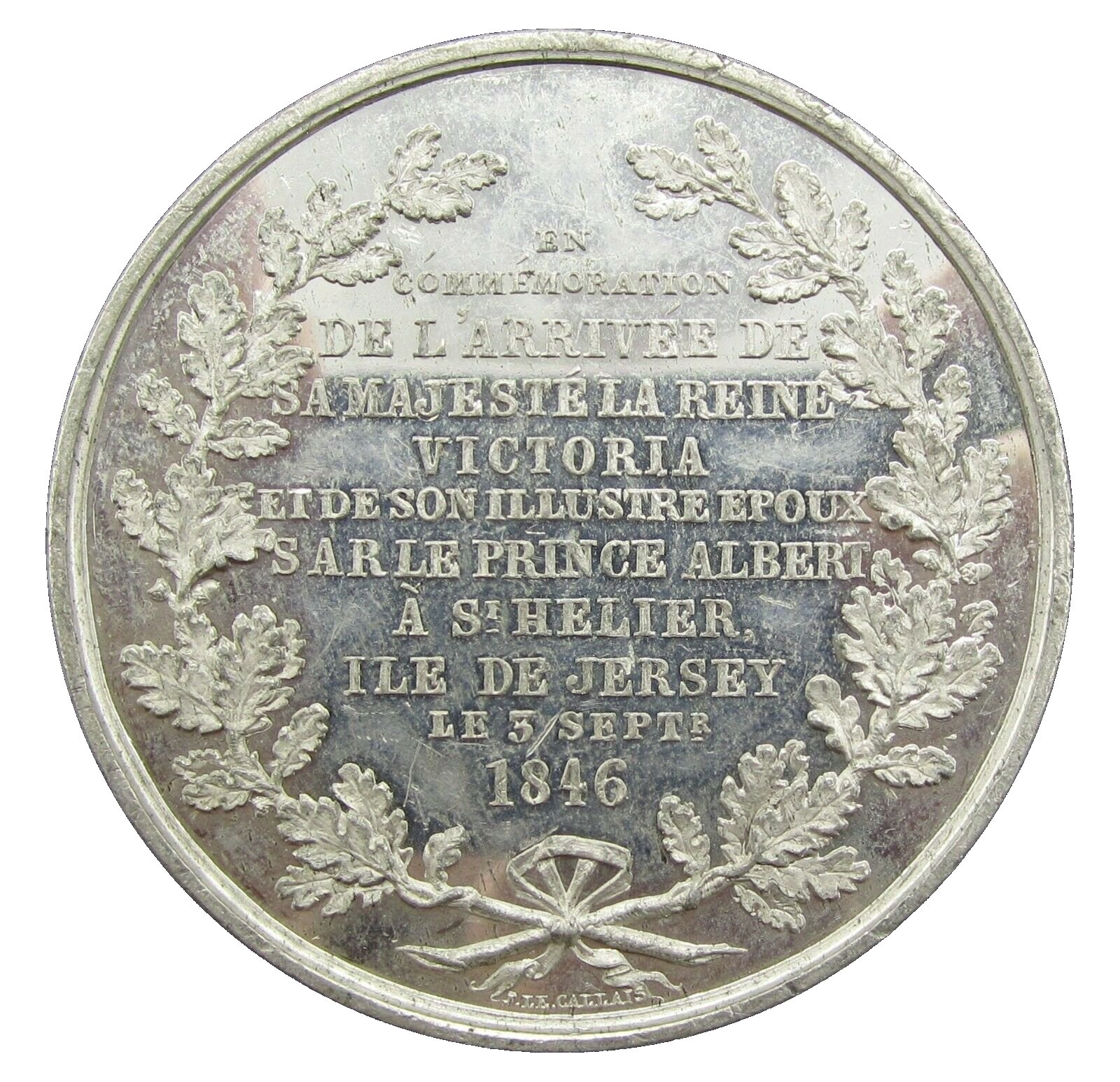

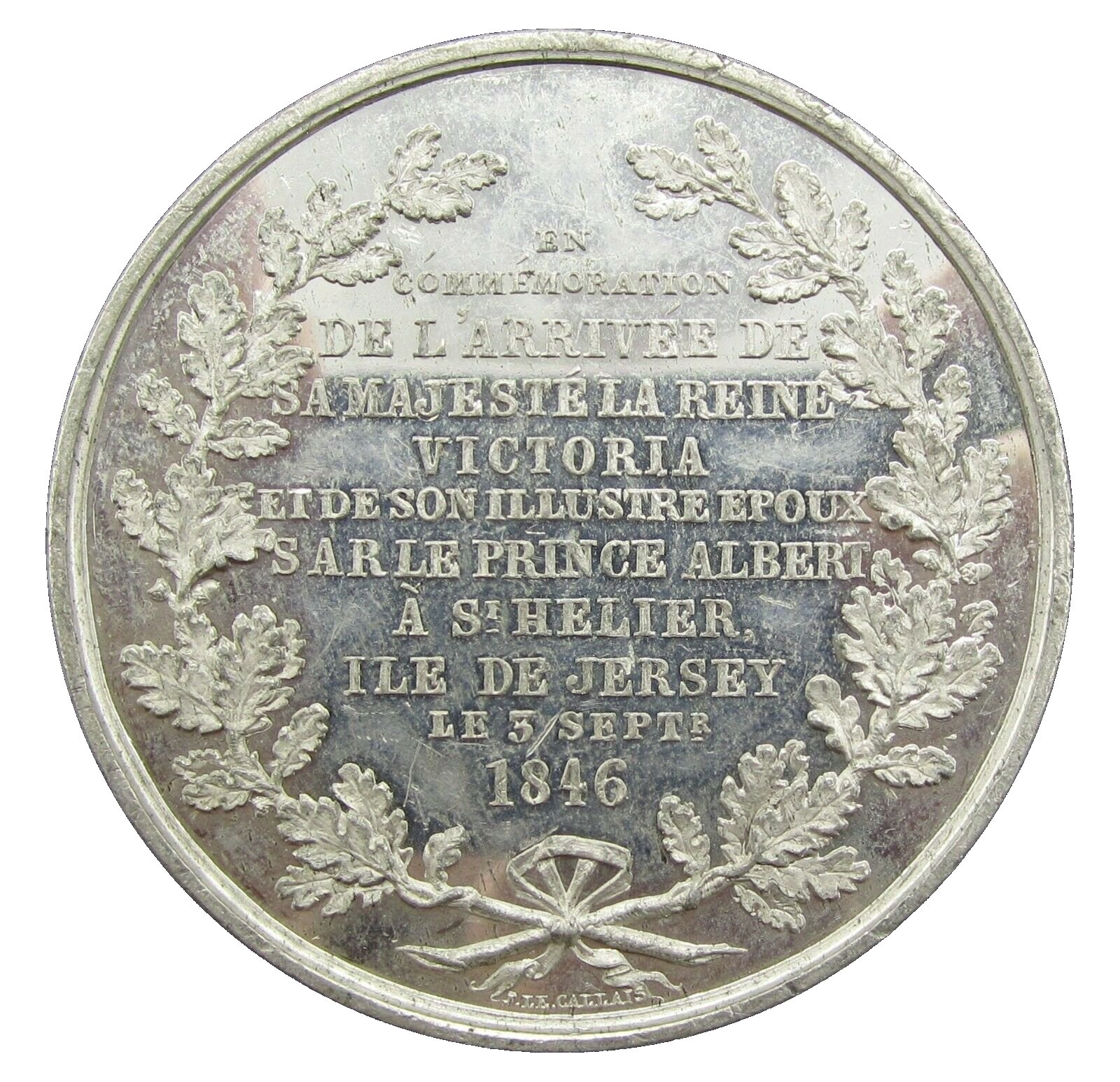

| This medal commemorates the 1846 visit of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. |

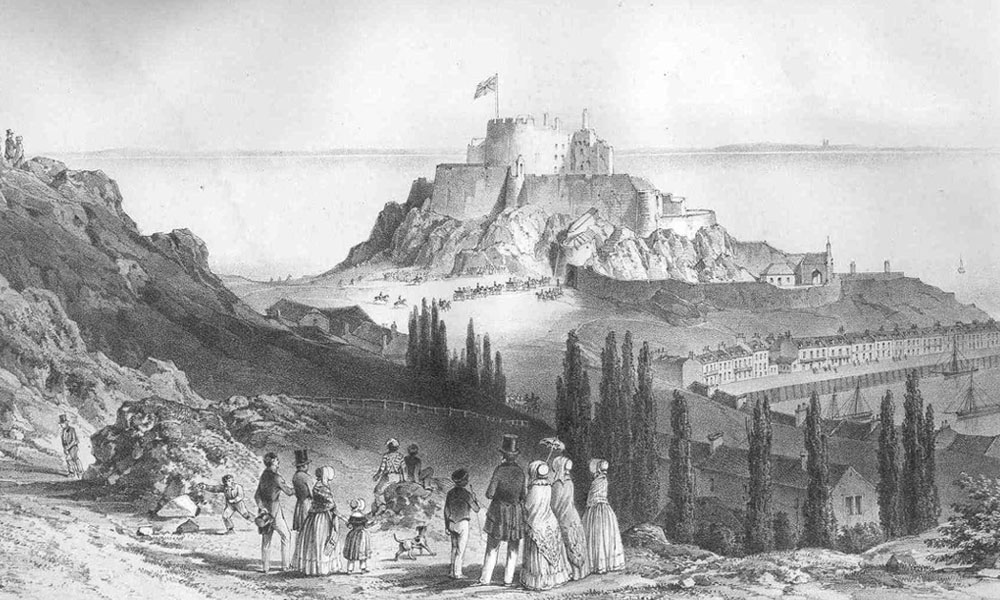

| From Appendix B of “The Channel Islands” by Paul Naftel 1862 |

|

| Appendix B continued |

|

| Appendix B continued |

|

|

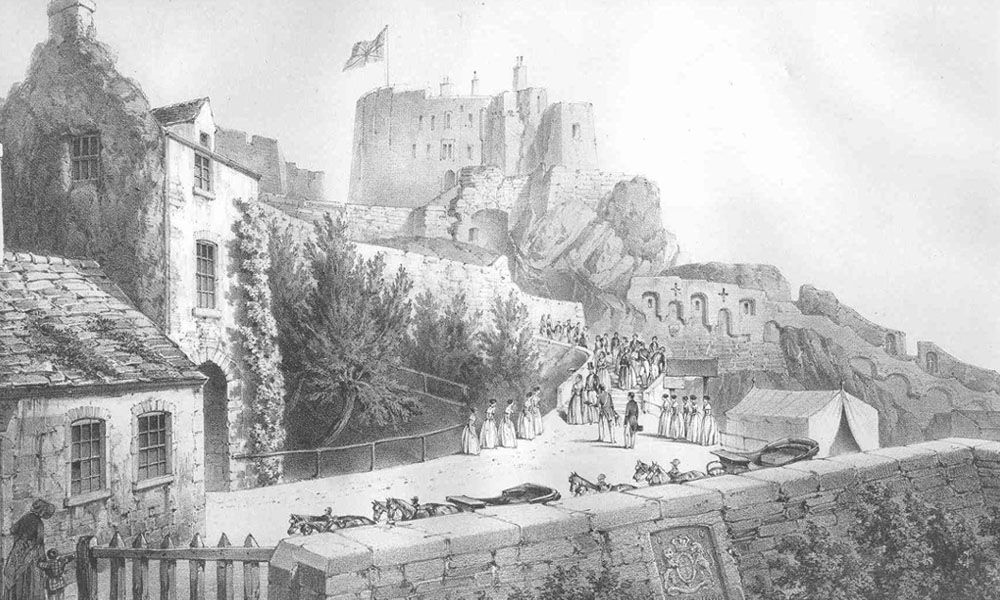

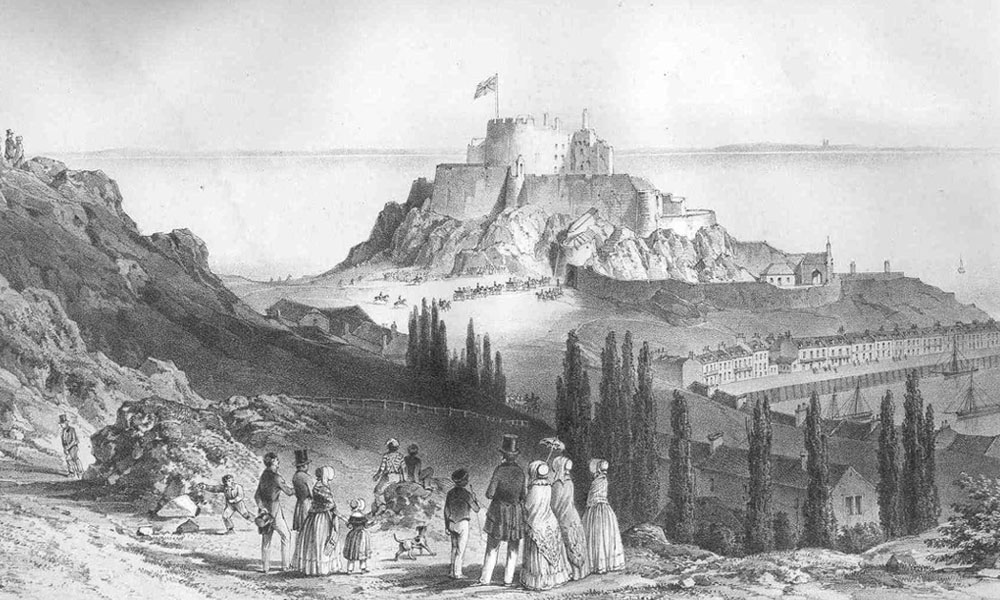

| Arrival of Her Majesty at Mount Orgueil by Philip John Ouless for the Queen's visit to Jersey in 1846 |

|

| The Obverse of the 1841 One Fifty-Second of a Shilling |

|

| The Reverse of the 1841 One Fifty-Second of a Shilling |

|

| The Obverse of the 1861 One Twenty-Sixth of a Shilling |

|

| The Reverse of the 1861 One Twenty-Sixth of a Shilling |

|

| The Obverse of the 1841 One Thirteenth of a Shilling |

|

| The Reverse of the 1841 One Thirteenth of a Shilling |

|

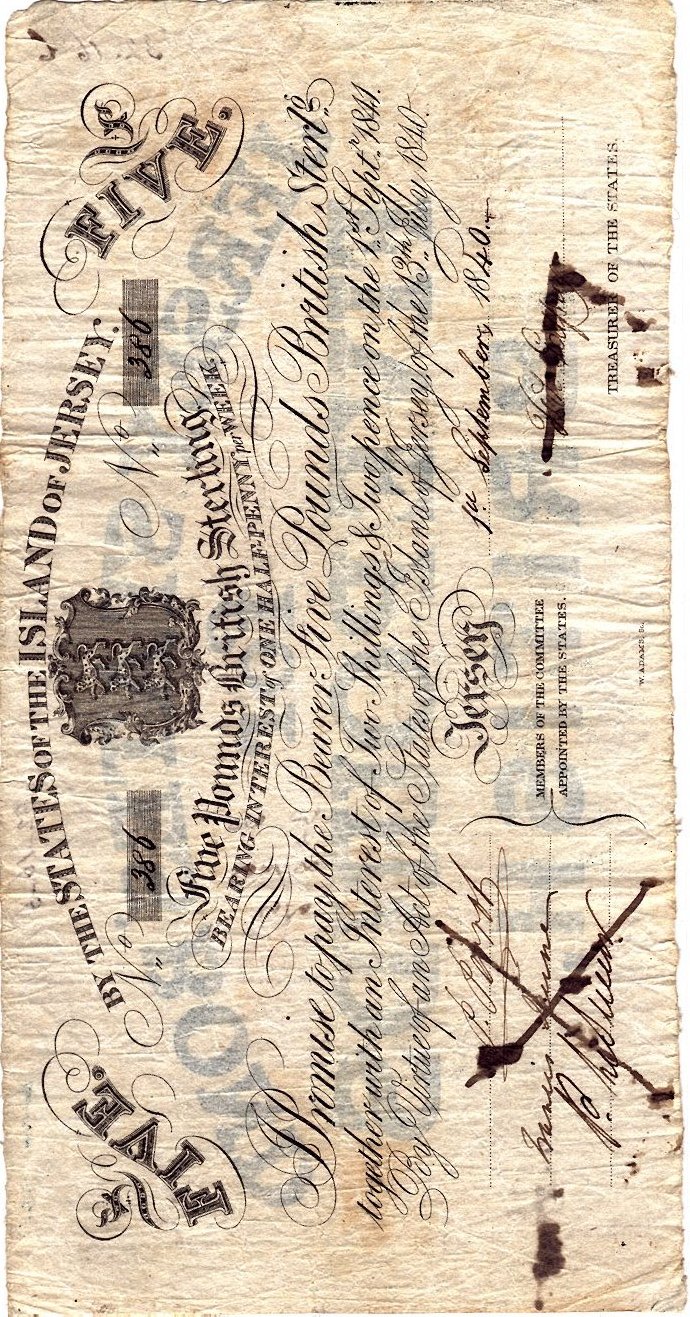

| A States Five Pounds Banknote of 1840 |

|

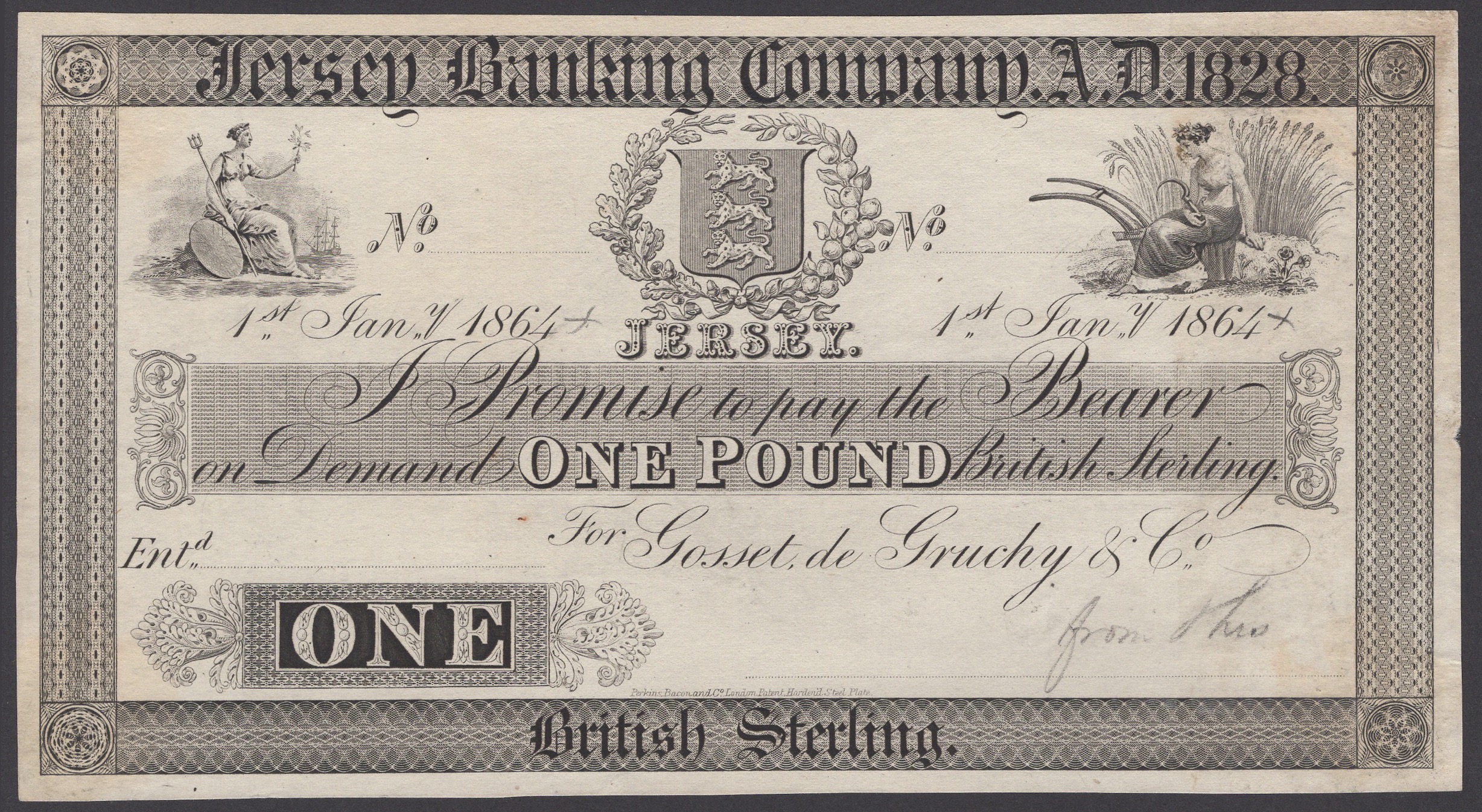

| One Pound Banknote Issued by the Jersey Bank in 1843 |

“The coinage and banking operations of Jersey offer some salient points to the curious. At the present, Bank of England notes, English and French gold and silver, and a local copper money form the staple currency. Formerly, French silver and copper, among the former of which the six-livre piece was prominent, were almost the only medium of exchange, and these coins, at the best of times, were very scarce. To supply this deficiency, early in this century the States of Jersey had three- shilling and eighteen-penny pieces, of local value, coined at the Royal Mint, but these were withdrawn in 1834. The insular currency was framed on the old French system—the sol or sou being a halfpenny, twenty sols one livre, and twenty-four livres one Louis d'or. In the Extentes, or Royal Rent Rolls, as well as in private account books of the olden time, reference is made to deniers and liards—one the twenty-fourth, the other the quarter of a sol. In the Guernsey special coinage the latter exists, and is almost as great a curiosity in its way as the new French centime; the former never was a coin, but merely a hair-splitting instrument of computation. Monnoie d'ordre appears in the publication of some fines in the last century. This had the effect of raising the livre fifty per cent., by means of an order in Council, dated 1729, and was iniquitously procured by certain local capitalists to depreciate the value of real property. The term is used in contradistinction to the livre tournois, or cours de France. Before 1841, the numismatist whose ambition did not rise higher than copper would have made hay triumphantly in Jersey, for it seemed that the Island was the universal refuge for all the “browns” of the universe. Imported wholesale, as a profitable speculation, by the native sailors from every country in the world, the Jersey people were so cosmopolitan in their ideas of what constituted a penny or a halfpenny, that flat discs of metal, innocent of die, passed freely in the ruck of this motley circulation. However, in the year mentioned, the Crown waived its prerogative, and permitted the States to issue its own pence, halfpence, and farthings. These, in accordance with the local system of calculation, were struck at the rate of thirteen pence to the English shilling, being a premium of 8 1/3 per cent, in favour of the latter. With the additional advantage of the Jersey pound avoirdupois, being 17 ½ ounces, money went far, but although the latter still remains as a boon to the buyer, almost all articles of necessity and luxury are bought and sold at English rates, or at so much “British!” as the Jersey Rothschildren say. |

|

| Lieutenant-Colonel Dixon R E presenting the Visitor's book to Her Majesty by Philip John Ouless for the Queen's visit to Jersey in 1846 |

|

| From “The Gossiping Guide to Jersey” by J. Bertrand Payne, 1865. |

|

| From “The History of Guernsey; with Occasional Notices of Jersey, Alderney, and Sark, and biographical Sketches” by Johathan Duncan, London 1841. |

From Appendix B of “The Channel Islands” by Paul Naftel 1862

|

This medal commemorates the 1846 visit of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. An 1859 newspaper article describing the visit.  Arrival of Her Majesty at Mount Orgueil by Philip John Ouless for the Queen's visit to Jersey in 1846 Cork Constitution (Cork, Republic of Ireland) - Monday 15 December 1862 The following have been sent to us as extracts from the letter of friend: Jersey Habits, &c.

Dear C. - Some little time ago you asked me to describe Jersey and its inhabitants. Well, as far as Jersey goes,

if you look in the Encyclopedia or any book of that sort you will get much better account of it than I can give.

However, I will able to tell you something about the manners, &c., there.

Women decidedly predominate, there being at least ten women to one man,

and a natural consequence there is an immense deal scandal there.

A few days ago I was at a party; the hostess had a very pretty daughter, and I had rather a jolly night.

The next day I went to pay my respects, and immediately it was rumored that I was going to be married to her.

Rather pleasant that. They give thirteen pence for a shilling here, and to new comer that is rather puzzling.

I was witness of very amusing incident the other day. A Paddie came into the of a hotel and asked for a noggin of whiskey.

It was handed him by a very pretty girl, and he put down a shilling.

To his great astonishment and delight twelve pence was handed in change.

He looked at it and the girl, and asked if that was right. The girl said perfectly so, and he turned to a comrade and said

"Arrah, jewel, sure this is beautiful place - they give whiskey for nothing;" and went away in great delight.

He was very much astonished, however, when he heard that they gave thirteen pence for shilling,

and that they were not so liberal in other matters.

|

From “The History of Guernsey; with Occasional Notices of Jersey, Alderney, and Sark, and biographical Sketches” by Johathan Duncan, London 1841. |

|

A proof/specimen banknote of the Jersey Banking Company dated 1 January 1864. On 11 January 1886, a notice appeared above the door of the Jersey Banking Company: "Unforeseen circumstances have compelled the bank to suspend payment". |

|